Harper Oreck:

As the morning lifts darkness from the village, I feel myself rise off my mat and watch my feet slide into my sandals, notice the fire starting as my fingers light the kindling, observe my hands fastening the knot on my wrapper. My son wakes, shifting in his corner, and arms that look like my own reach down to pick him up. I watch my limbs move, see them perform the mechanisms of morning, and feel only a dull ache spreading in my stomach.

When I begin to walk, leaving the village dusty and dry as I found it, a delegation of my mother’s brothers accompany me. Okonkwo will receive many gifts: in addition to palm wine, they bring honor, delivered through a satisfactory wife and child. As we move along the path, my son’s cries rise from the swaddle I hold limply against my chest. We pass the tree split by Agbala’s lightning and I remember the feeling of rocks cutting into the soles of my feet and fire lighting up my chest as I left my first husband and ran to Okonkwo. I catch a glimpse of the dry riverbed and think I see Okonkwo and I sitting with our feet in the water, both young and full of life. We emerge from the trees, and I face the village and recall the evacuated bodies of my children and the slow sting of saltwater dripping down my cheeks into the desert floor beneath them.

When Okonkwo greets us, he embraces my mother’s kinsmen and suggests that the men retire to his obi to exchange gifts and stories. He leaves without looking at his son, still rustling at my breast. When he turns, a throng of village women huddle around the baby: they marvel at the glow of his skin and the roundness of his cheeks, but their hushed voices are reminiscent of the years they spent whispering about my poisoned womb.

Bibliography

Image #1: A sculpture of Ani (also known as Ala,) the Igbo goddess of fertility. http://www.africaresource.com/rasta/sesostris-the-great-the-egyptian-hercules/ani-the-mother-of-the-igbos-the-many-manifestations-of-ishtar/

Image #2: An Igbo woman carries twins. In Ibgo villages, villagers often expelled twins, thinking them evil, and left them in the forest to die. http://www.bookdrum.com/books/things-fall-apart/9780385474542/bookmarks-151-175.html?bookId=1657,

Image #3: A woman wears jigida, which are strands of decorative beads traditionally worn by Igbo women as symbols of femininity. https://www.etsy.com/listing/93675492/jigida-traditional-african-waist-beads,

Image #4: A painting by Twin Seven Seven, a famous Nigerian painter. The painting depicts spirits of Abiku, children who die before adolescence, being healed. http://www.dailyartfixx.com/2012/07/25/twins-seven-seven-painting/

Image #5: A drawing of a spirit leaving the body of an okbanje, a child who dies then repeatedly revisits his mother, is reborn, then dies again. https://whenthingsfallapartigboreligion.wordpress.com/

Brennan Shin

It has been 3 years since I have been living in my father Okonkwo’s household. I have grown close to the family and especially close with my brother, Nwoye. I believe that since my arrival Okonkwo has been more pleased with Nwoye; he has been more inclined to take masculine tasks ever since the first month of my arrival. Although Nwoye has been more pleased with father’s attention, I have noticed that his eyes look off into the distance and shut out father’s voice when he shares tales of bloodshed and stories of battle. I would hear Nwoye at night whispering his mother’s folktales about the tortoise and his wily ways, and of the bird eneke-nti-oba who challenged the whole world to a wrestling match.

It has been 3 years since I have been living in my father Okonkwo’s household. I have grown close to the family and especially close with my brother, Nwoye. I believe that since my arrival Okonkwo has been more pleased with Nwoye; he has been more inclined to take masculine tasks ever since the first month of my arrival. Although Nwoye has been more pleased with father’s attention, I have noticed that his eyes look off into the distance and shut out father’s voice when he shares tales of bloodshed and stories of battle. I would hear Nwoye at night whispering his mother’s folktales about the tortoise and his wily ways, and of the bird eneke-nti-oba who challenged the whole world to a wrestling match.

Whenever we worked around the house and Nwoye’s mother sang songs, I would look at Nwoye as he closed his eyes and rocked himself back and forth to the beat of his mother’s hums. Whenever father comes to check up on us, Nwoye would immediately open his eyes and quickly work. He would say, “Mother! Quiet down, you are distracting ikemefuna and me. Do you see any children here? There is no need for such childish folktales." I could hear the fierceness in his words, but I could not see the fierceness in his expression or eyes. My father would be pleased with my brother’s remarks, for he believed that if Nwoye was more masculine, he would make a great man of the house when my father joins the ancestors.

The next morning nine men dressed in clothing as if ready to travel to a nearby village greeted my father and me. They made me carry a clay pot filled with wine. We started to walk out of the compound and into the outskirts of the forest. All I could see was green, and a dirt trail that seemed to wind on for eternity. The men talked about their wives and ridiculed some effeminate men who refused to go out with them.

The next morning nine men dressed in clothing as if ready to travel to a nearby village greeted my father and me. They made me carry a clay pot filled with wine. We started to walk out of the compound and into the outskirts of the forest. All I could see was green, and a dirt trail that seemed to wind on for eternity. The men talked about their wives and ridiculed some effeminate men who refused to go out with them.

As the hours passed and the sun has risen to its peak, we encountered a road that was wide enough to fit two people. My father told me to lead out of everyone. Everyone went silent when we started to walk on this road. I had an eerie and ominous feeling that was stuck at the bottom of my stomach. I continued to walk and heard footsteps behind me. The silence, the thickness of the forest, and the breath of the man behind me started to make me anxious. I decided it was ok because I trust my father. I was never close to my real father, but Okonkwo, I trust.

I started to think about my 3 year old sister, no, 6 year old sister. She must be very big by now, is her smile still the same? Does she even remember me? I then began to ponder about how my mother might react when she sees me. How she would yelp in excitement and hug me. I played this image in my head on repeat.

As we continued to walk on the path, my thoughts were interrupted by the man behind me who was clearing his throat. I looked back, “Keep walking” the man growled. The way the man looked at me sent a shiver down my spine. I then realized I haven’t seen my father in the last hour, why was he at the rear of the group? I heard a loud unsheathing of a machete behind me. When I looked back, the man who barked at me cut into my right shoulder as I dropped the pot of wine. Clutching my right shoulder in pain, I ran to my father. “My father, they have killed me!” I exclaimed. Looking at him for help as I kneeled in front of him. When I looked up into my father’s eyes, I could see a soft and fond expression on his face. He unsheathed his machete and brought it up over his head. I could feel tears streaming down my face as I realized what was to come of my fate. The last thing I saw was my father bringing his machete down upon me.

My Father’s Body (Nwoye)

When I heard the news today, I was not surprised.

My father was the kind of man who never found anything to be good enough, especially not me. He always wanted me to be a wrestler - a man comfortable with blood and senseless violence.

When I think back on where my father truly went wrong, I am always first reminded of the day Ogbuefi Ezeudu came to visit, walking solemnly through our compound, leaving an air of unease behind him. The next morning, my father left the house around noon with Ikemefuna. Our compound was near silent, waiting and hoping. My father came back late, long after the moon had risen into the black night. Ikemefuna was not with him. I knew what he had done. I sat there, limp, not even wishing anymore that my father might be innocent. I knew he was too weak for mercy.

Soon after, Ezeudu died. As the cannon and the ekwe broke the morning sky, women began to wail and men grabbed their ceremonial dress and their weapons. They ran about the village, giving a fierce and violent warrior’s salute. After the last, most terrifying egwugwu had come to pay his respects, the final frenzy begun. It was cut short, though, when a shot fired. My father’s gun had gone off, killing a boy. He was exiled to Mbanta.

I first saw the missionaries in while we were in Mbanta. Everyone gathered around as the white man walked into the village, accompanied by men who spoke a strange dialect. The man who translated for the white man began to tell us stories about a son who was also a father and a god. None of the village men took him seriously, laughing and joking. My father, however, was out to pick a fight, challenging the man when he said that the gods and the ancestors did not exist, grumbling off when it was clear none of the other men wanted violence. I lingered after he left, still curious about the white man. The missionaries began to sing. Suddenly, I felt drawn to them, as if their singing was a joyful answer to my father’s abrasive confrontations. I stood, enthralled, until they stopped, even as the people dispersed, almost believing I could hear Ikemefuna among them.

I longed to go beyond our compound walls, to meet the Christians and hear them singing again. Even as everybody laughed when they built their church in the Evil Forest, I believed. I was proven right when, after 28 days, it was still standing. One day, I finally ventured out to talk with the Christians. When I returned to the compound, my father knew. He began to choke me and beat me, demanding to know where I had been, as if it was not obvious, until the wives intervened. I walked out and never came back, seeking refuge in the church, where the priest and the congregation welcomed me.

I will not go to see my father’s body. When they give him an outcast’s burial, I will not go. I will sit in the church and pray for his soul to be clean of sinful pride.

Bibliography:

- http://africaawaken.com; Young Igbo men wrestling

- http://www.nairaland.com/1005808/igbo-architecture-ulo-ome-nigbo; An Igbo Mbari house - a sacred structure, an example of Igbo architecture

- http://jonesarchive.siu.edu/?page_id=486; An egwugwu

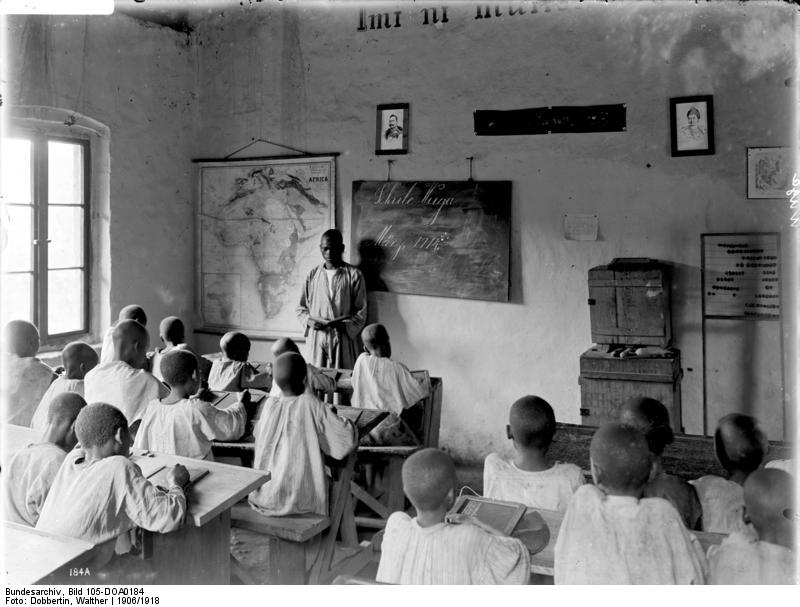

- http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2014/january-february/world-missionaries-made.html; Christian missionaries in Nigeria

- http://www.nairaland.com/1005808/igbo-architecture-ulo-ome-nigbo/5; The wall of an Igbo compound

Helen Deverell

Akunna’s Point of View

I know what Okonkwo thought of me. In his mind, my intellect was comparable to that of one of his wives. I was womanly, weak, and cowardly. I know that he had no respect for a man like me; he did not understand my intentions. Okonkwo was not like Mr. Brown. Mr. Brown appreciated my motives, leveled with my religion, and respected my people. Who was Okonkwo to try and defend Umuofia from the very people who had come here to help us? Skin color is clearly no marking of relation, for I felt more like a brother to Mr. Brown than to Okonkwo. In threatening Mr. Brown, Okonkwo became a foreigner to me, and I lost all of my dwindling respect for him.

Competition had always been in Okonkwo’s blood. Ever since the dawn of our faux friendship, I knew that, in Okonkwo’s mind, we would be competing for every title worth having. When Okonkwo won his first wrestling match, he made sure to come to my obi and tell me about his achievement personally. He did so under the guise of inquiry about my father’s health, but I knew of his true motives. For these reasons, I did not mourn, nor did I protest, when Okonkwo’s exile was determined. He should not have been so clumsy with his gun. In truth, I was relieved when he left. Okonkwo was a strong leader, and had originally been a positive influence on the people of Umuofia. But, in recent years, I had watched the light fade from his eyes. Violence became his immediate response to even the littlest of disputes. He was a disaster waiting to happen.

When the white men first showed up, I was sceptical along with everyone else. I had not seen anyone of this nature before, and I had no idea what they planned on doing to Umuofia. I was treated with slight condescension from the white men, but they had done no harm and began to seem genuinely interested in the bettering of our clan. Their trading posts helped to bring money into our village, and they built a hospital to heal and a school to educate. Mr. Brown told us that having a proper Christian education was of utmost importance. He said that, if we did not send our children to school, less sympathetic white people who were able to read and write would come to Umuofia and overpower us. Many people, including Okonkwo’s son, went to school or began to learn how to teach, heeding the advice of Mr. Brown. So, when Okonkwo returned from exile, he was furious at the changes that had taken place while he was away. He had no way of understanding the progress that we had made; he was simply offended that his position was no longer important, that violence was no longer the way of our men. Mr. Brown and I talked about violence. In the white man’s world, violence is not so easily called upon, not so quickly resorted to. In Christianity, as he called it, people do not follow the law of tradition. We talked about religion as well. I told him about Chukwu, and he told me about his God. Both must be approached with equal parts fear and respect. I told Mr. Brown that he and his kotma were like God’s messengers. I told him that we had similar roles in the Igbo religion. We were not so different after all, Mr. Brown and I. After our conversation, I once watched him chastise his clan for treating my people poorly. Not every white man that he had brought was as respectful as he was. I sympathized with him, however, for not every Umuofian had been accepting towards the white men either.

I knew enough to expect rage from Okonkwo when he found out Nwoye was training for a position in the white man’s world. Afterall, Okonkwo had always regarded Nwoye as womanly, as a disappointment, and what more feminine than the role of a teacher. Mr. Brown, however, did not know of this. He had good intentions in informing Okonkwo of his son’s path, and had no way of knowing about Okonkwo’s temper. When Mr. Brown told Okonkwo about Nwoye’s training, he was met with anger and extreme threats of the very violence the white men hoped to avoid. Mr. Brown, sad and ill, was forced to leave Umuofia. I will never forgive Okonkwo for this. On the day that Mr. Brown left, I lost a friend, and Umuofia lost stability. Things began to fall apart.

Bibliography

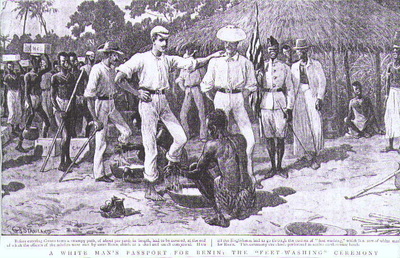

Harris, Alice Seeley. When Harmony Went To Hell. Digital image. Superselected. N.p., 6 Mar. 2014. Web. 17 Oct. 2016. <http://superselected.com/when-harmony-went-to-hell-congo-dialogues-the-tragedy-of-colonialism/>.Kjerland, Kirsten Alsaker., and Bjørn Enge. Bertelsen. Navigating Colonial Orders: Norwegian Entrepreneurship in Africa and Oceania. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.By This Time, as the Story Passes from One Unnamed Narrator to Another, the Reader Has to Hold the Story in Place and Identify Who Is Speaking Not by Name but by Voice and the Events Being Described. So on the Contrary, This Is a Book about Reading. That. "Afraso." Africa Is a Country. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2016. <http://www.afraso.org/en/aggregator/sources/7?page=42>. Mbuli, Rene. "The Colonial Heritage - in Africa." Action for Peace and Development (ASSOPED) Blog:. N.p., 01 Jan. 1970. Web. 17 Oct. 2016. <http://assoped.blogspot.com/2011/04/colonial-heritage-in-africa.html>."White Africans of European Ancestry." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2016. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Africans_of_European_ancestry>.

Brennan Shin

10-13-16

Ms. Hume

English II

Ikemefuna

Whenever we worked around the house and Nwoye’s mother sang songs, I would look at Nwoye as he closed his eyes and rocked himself back and forth to the beat of his mother’s hums. Whenever father comes to check up on us, Nwoye would immediately open his eyes and quickly work. He would say, “Mother! Quiet down, you are distracting ikemefuna and me. Do you see any children here? There is no need for such childish folktales." I could hear the fierceness in his words, but I could not see the fierceness in his expression or eyes. My father would be pleased with my brother’s remarks, for he believed that if Nwoye was more masculine, he would make a great man of the house when my father joins the ancestors.

After a long day of working on the wall and catching locusts, my brother, my father and I were drinking copious amounts of palm-wine. Nwoye and I have been challenging each other as to who has finished more of the wall. Nwoye said that I would have done more if I weren't so tired all the time.

I retorted, “I wouldn’t be so tired if you didn’t hum mother’s songs all night long.” My father shot Nwoye a look of disapproval.

My father got up from his seat when Ogbuefi Ezeudu came in. “Ogbeufi my elder, what brings you here? Please join us in our meal.”

Ogbeufi said, “No, I am not here for a meal Okonkwo, I am here to speak with you.” Ogbeufi said as he looked at me. “Let us talk outside”, he said as he was still watching me.

As soon as the two men shuffled out of the room Nwoye asked, “What do you think he wants with father?” he said with wide eyes,

“I don’t know” I answered. But I had a gut feeling it had something to do with me.

I retorted, “I wouldn’t be so tired if you didn’t hum mother’s songs all night long.” My father shot Nwoye a look of disapproval.

My father got up from his seat when Ogbuefi Ezeudu came in. “Ogbeufi my elder, what brings you here? Please join us in our meal.”

Ogbeufi said, “No, I am not here for a meal Okonkwo, I am here to speak with you.” Ogbeufi said as he looked at me. “Let us talk outside”, he said as he was still watching me.

As soon as the two men shuffled out of the room Nwoye asked, “What do you think he wants with father?” he said with wide eyes,

“I don’t know” I answered. But I had a gut feeling it had something to do with me.

The next day while working, my father told me that I will be taken home.

I was immediately shocked with joy, “Back to Mbaino? Back to my mother and sister?” I asked. My father gave a slight nod with a stern and stoic face.

I couldn’t contain my joy as I leaped towards him and wrapped my arms around him. “Ikemefuna!” he said in a surprised but stern manner. He shoved me away and told me to get back to work. I did not mind his shove for I was too happy to care.

I was immediately shocked with joy, “Back to Mbaino? Back to my mother and sister?” I asked. My father gave a slight nod with a stern and stoic face.

I couldn’t contain my joy as I leaped towards him and wrapped my arms around him. “Ikemefuna!” he said in a surprised but stern manner. He shoved me away and told me to get back to work. I did not mind his shove for I was too happy to care.

As the hours passed and the sun has risen to its peak, we encountered a road that was wide enough to fit two people. My father told me to lead out of everyone. Everyone went silent when we started to walk on this road. I had an eerie and ominous feeling that was stuck at the bottom of my stomach. I continued to walk and heard footsteps behind me. The silence, the thickness of the forest, and the breath of the man behind me started to make me anxious. I decided it was ok because I trust my father. I was never close to my real father, but Okonkwo, I trust.

I started to think about my 3 year old sister, no, 6 year old sister. She must be very big by now, is her smile still the same? Does she even remember me? I then began to ponder about how my mother might react when she sees me. How she would yelp in excitement and hug me. I played this image in my head on repeat.

As we continued to walk on the path, my thoughts were interrupted by the man behind me who was clearing his throat. I looked back, “Keep walking” the man growled. The way the man looked at me sent a shiver down my spine. I then realized I haven’t seen my father in the last hour, why was he at the rear of the group? I heard a loud unsheathing of a machete behind me. When I looked back, the man who barked at me cut into my right shoulder as I dropped the pot of wine. Clutching my right shoulder in pain, I ran to my father. “My father, they have killed me!” I exclaimed. Looking at him for help as I kneeled in front of him. When I looked up into my father’s eyes, I could see a soft and fond expression on his face. He unsheathed his machete and brought it up over his head. I could feel tears streaming down my face as I realized what was to come of my fate. The last thing I saw was my father bringing his machete down upon me.

Bibliography

http://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1456114733i/18190809.jpg

http://media.premiumtimesng.com/wp-content/files/2012/11/Machete.png

YSiegel

Mrs. Hume

English II

10 - 25 - 16

The Struggle of Mr. Smith

A loud horn burst through the air. Over and over again, my ears struggled to absorb the sound. Then, silence and the sound of waves. I longed for that sound to shake my core for more than a month. Then, without warning I was awakened by the most pleasant sound. The boat horn once again pierced the air to welcome me to my new life.

Now, I am satisfied with my success. New children of god are blessed by the light of forgiveness every day. The people abandoned by their own upbringing are enveloped in the warmth of acceptance due to my work. People may now be skeptical, but, in the end, they too will see the way of the righteous and join me in my quest to purge their false gods from these tainted lands. Those who do not join me will be damned to eternal peril. Their struggle will all be in vain as I...

“What is that damned noise? It so loud it's disrupting my writing”

“It is the egwugwu reverend. They are angry at Enoch for interrupting a ceremony.”

“Who is angry?”

“The egwugwu. The elders of the clan dressed up as ancestral spirits.”

“My word! I'm going to go put an end to these ridiculous games.”

“Reverand! They are following me!” Enoch said,

“Why my good man?”

“I have killed their god in the name of the church. Please let me in."

“Thank you, reverend.”

… The accusers of our faith came to the church later and wanted to burn down the church for Enoch’s actions...

“Tell the white man that we will not do him any harm. Tell him to go back to his house and leave us alone. We liked his brother who was with us before. He was foolish, but we liked him, and for his sake we shall not harm his brother. But this shrine which he built must be destroyed. We shall no longer allow it in our midst. It has bred untold abominations and we have come to put an end to it. Fathers of Umuofia, I salute you. You can stay with us if you like our ways. You can worship your own god. It is good that a man should worship the gods and the spirits of his fathers. Go back to your house so that you may not be hurt. Our anger is great but we have held it down so that we can talk to you." (Pg. 190)

"Tell them to go away from here. This is the house of God and I will not live to see it desecrated."

(Pg. 190)

(Pg. 190)

… Scoundrels! Miscreants! Why must they deface the house of god? For their sins the Almighty Father will punish them with fire and brimstone and they will eternally suffer in the depths of hell. The time for conversion without violence has come to an end. This now falls in the hands of the District Commissioner. These infidels will be brought to justice through whatever means necessary, even actions unholy.

Tyson

He named me Nwoye after the second day of the week. I am Okonkwo’s first born son, and I can not escape the feeling of being insufficient. I have never felt comfortable being myself. My dad says he wants me to be stronger, but deep down I know that he only wants to see himself in me. He gave me life, but it was never really mine to live.

Feeling lost I set out to find an alternate father figure, and I found him in my brother, Ikemefuna. He showed me it is possible to love someone outside of my family. In my father’sw1vv opinion feeling love and compassion would be too feminine. He has taught me that not all power comes from physical strength. However, the strong relationship my brother and I have was cut short when my father murdered him. Ikemefuna’s murder made me question my father’s ability to feel love, and I realised that I have no desire to be like him.

In mourning my brothers death I started to listen to the missionaries. They told stories and sang songs about love and acceptance. These stories were much less gory and evil than the those of my father. I began to practice Christian beliefs after my brother’s death just to get my mind off of things, but I found a father in God and strength in myself. Becoming a Christian gave me independence and hope.

@babynamescube. "Nwoye - Meaning of Nwoye Name, Nwoye Origin."Nwoye - Meaning of Nwoye Name, Nwoye Origin. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 Oct. 2016.

"Nwoye+and+okonkwo+relationship - Google Search."Nwoye+and+okonkwo+relationship - Google Search. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 Oct. 2016.

N.p., n.d. Web.

A Bond Between a Father and His Son; A False Sense of Trust

By: CAlonso

I remember my village and when I was a young boy being chased by the evil spirits that would run after all the young boys in our village. When I ran out of breath, I would hide under the little table in my father’s hut, but I was always found because when the spirits would walk around I would not be able to contain my giggles.

I remember my village and when I was a young boy being chased by the evil spirits that would run after all the young boys in our village. When I ran out of breath, I would hide under the little table in my father’s hut, but I was always found because when the spirits would walk around I would not be able to contain my giggles.

One day, I hid under the table, and my father with all of the village leaders walked into the hut. They seemed distraught as they spoke quietly and quickly. I held my breath and bit my lip; the urge to laugh almost exposed my hiding spot. The council members spoke about a young man that had killed a woman near the river. They were discussing his punishment for this great offense. The eldest council who had not spoken rose his hand and said, “This young man will be killed with a pot full of kola nuts held above his head, so when he would be slain down to the ground the pot will crash and his death would be known to all who shut their eyes.” Silence overcame the room and they all left the hut.

One day, I hid under the table, and my father with all of the village leaders walked into the hut. They seemed distraught as they spoke quietly and quickly. I held my breath and bit my lip; the urge to laugh almost exposed my hiding spot. The council members spoke about a young man that had killed a woman near the river. They were discussing his punishment for this great offense. The eldest council who had not spoken rose his hand and said, “This young man will be killed with a pot full of kola nuts held above his head, so when he would be slain down to the ground the pot will crash and his death would be known to all who shut their eyes.” Silence overcame the room and they all left the hut.

I had not killed anyone nor would my father allow them to injure me. I am protected by the strong bond of a father and his son. Unless my father did not see me as his son, and I mean nothing to him. Yet those tedious days of planting yams and wrestling matches assured me of our relationship. Okonkwo has taught me to be a man. I have nothing to worry about. My life is in the hands of my father.

I had not killed anyone nor would my father allow them to injure me. I am protected by the strong bond of a father and his son. Unless my father did not see me as his son, and I mean nothing to him. Yet those tedious days of planting yams and wrestling matches assured me of our relationship. Okonkwo has taught me to be a man. I have nothing to worry about. My life is in the hands of my father.

Tension starts to spread amongst the group. The air feels thinner as I struggle to take a breath. Suddenly a cold shiver runs through my back. A crisp blade exposes my back; I feel empty when I cry out, “My father, they have killed me!” Okonkwo comes to comfort me and protect me. I feel his warm presence until I saw my reflection in his machete. I accept his blow and plunge onto the frozen floor. I stare at the shoes of my father and fall asleep.

Tension starts to spread amongst the group. The air feels thinner as I struggle to take a breath. Suddenly a cold shiver runs through my back. A crisp blade exposes my back; I feel empty when I cry out, “My father, they have killed me!” Okonkwo comes to comfort me and protect me. I feel his warm presence until I saw my reflection in his machete. I accept his blow and plunge onto the frozen floor. I stare at the shoes of my father and fall asleep.

Two mercenaries lugged the haggard body deep into the bush where no one would ever find him. The soon-to-be corpse’s limbs were as thin as the surrounding branches of the ohia, and his belly was as swollen as a kim-kim.

Two mercenaries lugged the haggard body deep into the bush where no one would ever find him. The soon-to-be corpse’s limbs were as thin as the surrounding branches of the ohia, and his belly was as swollen as a kim-kim.

“I am a peaceful man. I am a poetic musician. But, most of all, I am a proud father. I care not for blood. I care not for war. I care not for wealth. I care not for titles and fame. I have dreams and desires for a peaceful life, and...”

“I am a peaceful man. I am a poetic musician. But, most of all, I am a proud father. I care not for blood. I care not for war. I care not for wealth. I care not for titles and fame. I have dreams and desires for a peaceful life, and...”

Naked, without his wrapper, he stood in the middle of his village. There was a steady crescendo of muted whispers that turned into audible mockery as the villagers voiced their displeasure with the parasite. Suddenly, he was surrounded by hundreds of mask-like figures frantically dancing around him. They danced the Adamma, Omuru-onwa, Agbacha-ekuru-nwa, Nkwa umu-Agbogho, and Ikpirikipi-ogu. Finally, he saw an Ikenga mask sailing to the heavens, just out of his reach, heading towards Choukyou. Then a figure appeared to him in a far away haze. The visage of the god of war, Ikenga, came into focus.

Naked, without his wrapper, he stood in the middle of his village. There was a steady crescendo of muted whispers that turned into audible mockery as the villagers voiced their displeasure with the parasite. Suddenly, he was surrounded by hundreds of mask-like figures frantically dancing around him. They danced the Adamma, Omuru-onwa, Agbacha-ekuru-nwa, Nkwa umu-Agbogho, and Ikpirikipi-ogu. Finally, he saw an Ikenga mask sailing to the heavens, just out of his reach, heading towards Choukyou. Then a figure appeared to him in a far away haze. The visage of the god of war, Ikenga, came into focus.

“Why would you choose the flute over the machete?” Ikenga asked. “The Igbo are proud warriors. You bring disgrace upon our people, and you bring shame upon your family and your respected son.”

“Why would you choose the flute over the machete?” Ikenga asked. “The Igbo are proud warriors. You bring disgrace upon our people, and you bring shame upon your family and your respected son.”

Unoka began to cry. He cried because of the immense pain. He cried because his own son did not love him. He mourned that his musical talents would be extinguished. He cried because no one would remember him after he died. He knew his fate was sealed. His final words escaped his dry lips, “Ikenga chim nyelum, taa oji.” (Ikenga, gift of my chi, participate in the offering). Slowly the weeping came to a halt, and Unoka cried no more.

Unoka began to cry. He cried because of the immense pain. He cried because his own son did not love him. He mourned that his musical talents would be extinguished. He cried because no one would remember him after he died. He knew his fate was sealed. His final words escaped his dry lips, “Ikenga chim nyelum, taa oji.” (Ikenga, gift of my chi, participate in the offering). Slowly the weeping came to a halt, and Unoka cried no more.

I can’t seem to get Ikemefuna’s voice out of my head. I hear it in the howling of the wind, the crackling of the fire, and even Mr. Brown’s sermons. I’ve been going to more and more of them lately, but every time he talks about the wonders of his God and the land of white men where he comes from, it just serves to remind of the fucked-up, backwards world I grew up in. I still live here in Umuofia, this land of heathen, but when I’m old enough, I’m going to be educated in Yurup, where Mr. Brown says everyone looks like him. Maybe I’ll even meet his Kween. He just can’t stop talking about her.

I can’t seem to get Ikemefuna’s voice out of my head. I hear it in the howling of the wind, the crackling of the fire, and even Mr. Brown’s sermons. I’ve been going to more and more of them lately, but every time he talks about the wonders of his God and the land of white men where he comes from, it just serves to remind of the fucked-up, backwards world I grew up in. I still live here in Umuofia, this land of heathen, but when I’m old enough, I’m going to be educated in Yurup, where Mr. Brown says everyone looks like him. Maybe I’ll even meet his Kween. He just can’t stop talking about her.

Until then, though, I’m going to have to continue among the pagans. The baby-killers, wife-beaters, and worshippers of false idols. Although my mother and sisters are heathen, I have hope for them because they are merely blind. Oblivious. I will bring them to Jesus’ light eventually. The one about whom I truly worry is Okonkwo the Heretic. I cannot dismiss him merely as ignorant because of his infuriating obstinance in the face of our Lord. If that man lays his hands on me one more time, I swear he will never see me again. Mr. Brown says Jesu Kristi is my true father.

Until then, though, I’m going to have to continue among the pagans. The baby-killers, wife-beaters, and worshippers of false idols. Although my mother and sisters are heathen, I have hope for them because they are merely blind. Oblivious. I will bring them to Jesus’ light eventually. The one about whom I truly worry is Okonkwo the Heretic. I cannot dismiss him merely as ignorant because of his infuriating obstinance in the face of our Lord. If that man lays his hands on me one more time, I swear he will never see me again. Mr. Brown says Jesu Kristi is my true father.

I have known Okonkwo would return for months, yet I cannot fathom that I will I finally see the man who killed not one, but two of my brothers. So long as he offers me hospitality, I will stay in his obi, but I will not talk to him or show him any respect beyond the traditional tribal salute. My feet feel heavier than baskets of yam after a generous harvest, but I must enter the house, must finally lay eyes on the man who has caused me so much pain that he can no longer call himself my father.

I have known Okonkwo would return for months, yet I cannot fathom that I will I finally see the man who killed not one, but two of my brothers. So long as he offers me hospitality, I will stay in his obi, but I will not talk to him or show him any respect beyond the traditional tribal salute. My feet feel heavier than baskets of yam after a generous harvest, but I must enter the house, must finally lay eyes on the man who has caused me so much pain that he can no longer call himself my father.

Hands around my neck. Oh God. Please protect me. I feared the worst, but I did not expect it to happen so quickly. I see Okonkwo’s mouth moving, presumably screaming profanity, but I hear no sound. Everything is moving slow. So slow. My arms and legs refuse to function. I can feel the hands tighten around my throat. The sour spittle flying onto my face. The cane descending toward my body. Shattering my ribs. I. Can’t. Breathe.

Hands around my neck. Oh God. Please protect me. I feared the worst, but I did not expect it to happen so quickly. I see Okonkwo’s mouth moving, presumably screaming profanity, but I hear no sound. Everything is moving slow. So slow. My arms and legs refuse to function. I can feel the hands tighten around my throat. The sour spittle flying onto my face. The cane descending toward my body. Shattering my ribs. I. Can’t. Breathe.

A Bond Between a Father and His Son; A False Sense of Trust

By: CAlonso

As the man who had cleared his throat drew up and raised his machete, Okonkwo looked away. He heard Ikemefuna cry, “My father, they have killed me!” as he ran towards him. Dazed with fear, Okonkwo drew his machete and cut him down. He was afraid of being thought as weak. (Achebe 61)

I listen to the loud pounding of the travelers’ footsteps around me. The thump thump thump syncs with my heartbeat as the silence allows thoughts to fill my head. Memories of my family remind me of my childhood and how I have grown.

A thundering cough interrupted my thoughts, and I returned to the laborious walk. My legs started to weigh. I felt like I was drugged with a delirious notion that made me believe that my own father would kill me just as my village killed the young man.

Bibliography

- https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/archives/2014/05/ -The village leaders meeting

- http://enaburg.com.ng/kolanut.html- Kola nut represents acceptance and unification

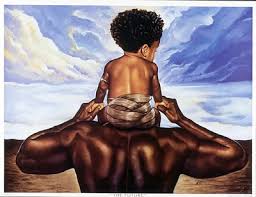

- www.pinterest.com/dionfreemind/afrikan-art/ -Father and his son

- http://www.metmuseum.org/connections/war_and_conflict -War and Conflict -Oba with Animals by:Nigeria; Edo peoples, court of Benin

Unlike Father, Unlike Son

By Jolah

“My name is Unoka. This must be a mistake. Please help me. Take me back to my home. Have you no mercy in your souls? I have done nothing wrong.”

“Nothing wrong? Shame on you! You are a disgrace to your village. You are lazy and wasteful. You are a debtor who owes many cowries. You have taken and sought no titles. You play the flute while others work and fight. You do not deserve to live. Umuofia is not a sanctuary for cowards.”

“I…I am not a coward.”

“Ha! If not a coward, then what are you?”

Unmoved, the men proceeded to kick his emaciated frame and left him to succumb to the harsh elements. Alone and dying from the ravages of his addictions, Unoka began to hallucinate. The whirling images in his head seemed as if he were viewing them through the lense of a kaleidoscope, continually changing focus in-and-out and from side-to-side. Not like the calming dreams produced when he would partake of gourds of palm wine and pinches of snuff, these were anxiety-provoking nightmares that challenged his soul.

Before Unoka could answer, the setting shifted once again. Okonkwo, his son, came running through the door of their obi, a satisfied grin plastered over his face having just defeated Amalinze the Cat in front of the adoring elders.

“I wish I could have seen him triumph over the Cat. He is much different from me, but that is his nature, and I respect our differences. If only he could respect my nature.”

Out of nowhere, Okonkwo’s grin transformed into a blood-thirsty glower as he lunged towards his father. Fangs sank deep into Unoka’s legs. Instantly, he returned back to consciousness, a hyena scratching his face and gnawing at his legs. Summoning the last ounce of his limited strength, Unoka fought back ineffectively. Blood dripped from the cuts on his face, his limbs quivered from exhaustion, and his skin burned in the oppressive heat as the hyena left him alone to die.

Bibliography

https://www.pinterest.com/bczerniewski/african-drums/ - a tradition Igbo drum called a kim kim

https://www.naij.com/949030-igbo-amaka-5-photos-will-make-fall-love-igbo-culture.html - a traditional Igbo flute called an Opi

https://www.igboguide.org/HT-chapter10.htm - Igbo Village

https://www.igboguide.org/HT-chapter9.htm - a masked Igbo god

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ikenga - statue of Ikenga the god of war

V. Swezey: The Reunion

Oh, Jesu Kristi. Jesu. There he is. The mere sight of his face sickens me. I’ll just salute him and keep walking. Keep walking. There’s my mother. Just keep walking. Maybe he does not know I have found the Church? He has to. God. Please help him see your Light. Please turn this sinner from his ways. I know he can be saved.

“Leave that boy at once!” That must be the voice of Jesu Kristi. I feel the grip loosening. My Lord has come to the aid of his sheep. If I make it out of the threshold, I will never enter this house again.

“Okonkwo Raising Ikemefuna.” http://durrikawkabantarek.blogspot.com/2012/04/defending-okonkwos-action-of-killing.html

“Ruins of Nigerian Colonial Church.” http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/03/god-s-country/306652/

“Modern Day Evil Forest”

“Nigerian Obi”

“The Light of Jesu as Nwoye Sees It”

http://getupwithgod.com/tag/prayer/page/3/

The seven years of my father’s exile were drawing to a close. Relief and pleasure were more and more common in my father’s face as the date drew nearer. I had watched my father’s sorrow when we moved here, and his regret as the years passed. To him it was a tragedy, time lost and wasted. I was only a child when we were cast out of our father's land because of the crimes he committed against our kinsmen; this is the home that I remember, the home that feels comforting and familiar. I have friends and family here, my life is here, but I will leave it, because the opinions of a daughter are not to be voiced or heard.

The seven years of my father’s exile were drawing to a close. Relief and pleasure were more and more common in my father’s face as the date drew nearer. I had watched my father’s sorrow when we moved here, and his regret as the years passed. To him it was a tragedy, time lost and wasted. I was only a child when we were cast out of our father's land because of the crimes he committed against our kinsmen; this is the home that I remember, the home that feels comforting and familiar. I have friends and family here, my life is here, but I will leave it, because the opinions of a daughter are not to be voiced or heard.

In preparation for our departure, we must provide a feast to thank our father’s mother’s kinsmen, and Okonkwo wishes to make it a grand feast. It is the job of the women to provide food like fish, palm-oil, and pepper, as well as harvesting the cassava tuber. Ekwefi, Ezinma and I rose very early one morning and carried our tools to the farm. The harvest would not take very long, for it had rained the night before and the the soil had been softened.

In preparation for our departure, we must provide a feast to thank our father’s mother’s kinsmen, and Okonkwo wishes to make it a grand feast. It is the job of the women to provide food like fish, palm-oil, and pepper, as well as harvesting the cassava tuber. Ekwefi, Ezinma and I rose very early one morning and carried our tools to the farm. The harvest would not take very long, for it had rained the night before and the the soil had been softened.

Despite her complaints, Ezinma worked diligently and without hesitation. It is these characteristics in her that made Okonkwo so fond of her. I was not blind; I could see that our father prefered my sister; he even preferred her over his sons, which is a rarity. Ezinma understands our father in ways that none of his other children do. I think this is why she seems so much older than I; she understands the goals and values of our father, the leader of our family, and often helps me understand them. I remember her telling me that we had to wait until we returned to our fatherland before getting married, even though there were already men that were interested in marrying us here, in our motherland. Our father had told her this and she had understood it, agreed with it. I am not so quick, I have always had trouble understanding our father’s actions, as many of my siblings do, but it is not my place to question my father’s authority .

Despite her complaints, Ezinma worked diligently and without hesitation. It is these characteristics in her that made Okonkwo so fond of her. I was not blind; I could see that our father prefered my sister; he even preferred her over his sons, which is a rarity. Ezinma understands our father in ways that none of his other children do. I think this is why she seems so much older than I; she understands the goals and values of our father, the leader of our family, and often helps me understand them. I remember her telling me that we had to wait until we returned to our fatherland before getting married, even though there were already men that were interested in marrying us here, in our motherland. Our father had told her this and she had understood it, agreed with it. I am not so quick, I have always had trouble understanding our father’s actions, as many of my siblings do, but it is not my place to question my father’s authority .

In a week's time my family will return to Umuofia and Ezinma and I will marry shortly thereafter. I have faith that Ezinma always be wise, she will chose a good husband and carry capable children. She will be the greatest that a woman can be. I am less sure about myself and my fate. I will follow the same path but it may lead me somewhere different, time can only tell if it is better or worse. I am not as strong or smart as Ezinma but I am Okonkwo’s daughter and all of Okonkwo children can find strength in Umuofia.

In a week's time my family will return to Umuofia and Ezinma and I will marry shortly thereafter. I have faith that Ezinma always be wise, she will chose a good husband and carry capable children. She will be the greatest that a woman can be. I am less sure about myself and my fate. I will follow the same path but it may lead me somewhere different, time can only tell if it is better or worse. I am not as strong or smart as Ezinma but I am Okonkwo’s daughter and all of Okonkwo children can find strength in Umuofia.

Marcela Becerra

Ms. Hume

English II

October 17 2016

Obiageli ( Okonkwo’s daughter)

Ezinma had begun to complain about the leaves dripping onto her back and wetting her. She disliked the water, I called her “salt” because of it, as if she was afraid that she would dissolve.

Sources:

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteKPieschala:

ReplyDelete“I knew he was too weak for mercy.”

“My father was the kind of man who never found anything to be good enough, especially not me.”

Katie brings Nwoye back to his childhood and writes about his memories of his father’s wrongdoings. This sets the stage for Nwoye’s acceptance of the Christian religion that she speaks to later on in her essay. My favorite part of her story was the ending. Nwoye’s (warranted) disrespect towards his father even after his death shows just how powerful his emotions were. This displays the resent that Nwoye feels towards his father, and his newly internalized belief in Christianity.

Bshin:

“I have noticed that his eyes look off into the distance and shuts out father’s voice when he shares tales of bloodshed and stories of battle”

Brennan examines the relationship between Nwoye and Ikemefuna, and the ways in which Ikemefuna picks up on Nwoye’s nuances and subtleties that he gives away when he hears his father speak about war and bloodshed. Ikemefuna gets to know Nwoye in no way that anyone has before, and accepts him for his nonviolent ways. He is extremely perceptive and receives Nwoye in a way that Okonkwo never has. Ikemefuna does not care that Nwoye is not overtly masculine; Nwoye is a brother to Ikemefuna nonetheless. Brennan’s story highlights the way that Ikemefuna seamlessly blends into Okonkwo’s family, making his death even more shocking and painful. Brennan’s story made me feel like Ikemefuna was an old friend, and I could really empathize with Nwoye as well. I understood the way Nwoye felt towards Ikemefuna: admiration and brotherly love, and I saw the slightly protective nature of Ikemefuna towards Nwoye. Ikemefuna did not seem like an outsider at all in Brennan’s story; he seemed like he had been part of the family all along.

HOreck:

“They tell me that my abdomen swells with triumphant fluids from the birth of my last child, but they cannot feel the specters of children as they make their homes inside my womb.”

“whispering about my poisoned womb. “

“I know my son will not live, and the burden of wondering falls from my shoulders.”

Harper shows the painful and dejecting nature of Ekwefi as she gives birth to a young boy. She cannot shake the haunting memories of her past miscarriages, and cannot bring herself to celebrate the birth of a son whom she knows will not live. Harper’s story shows the way that the Umuofian people receive Ekwefi, and how they act towards a woman with a “poisoned womb.” Because motherhood was the main accomplishment and carrier in African society, Harper shows how hard it is for a woman who feels she has failed. Towards the end of the story, Ekwefi has accepted her fate, and this brings her saddened peace.

VSwezey:

ReplyDelete“Until then, though, I’m going to have to continue among the pagans. The baby-killers, wife-beaters, and worshippers of false idols.”

Victory portrays Nwoye as someone who has just seen the light. With the help of Christianity, Nwoye now believes that this is the life that was meant for him. Victor shows how Nwoye finally breaks free from his father authority, losing all respect for the man he now calls Okonkwo. He views Christianity as more sane, reasonable, relatable, and humane than the traditions of Umuofia. In Victor’s writing, one can imagine Nwoye as a young man who is finally able to think for himself. Victor portrays Nwoye to be deeply religious, praying to “Jesu Kristi” for redemption for his father. Nwoye now wants to follow in the path of Mr. Brown as opposed to Okonkwo, and Victor shows the initial reasoning for Nwoye’s decision.

DLiddiBrown:

“I was blessed to live but destined to die.”

“I remembered an old song I used to sing and walked to the beat of each word.”

I think that one interesting aspect of Dash’s story is the fact that portrays Ikemefuna as someone who knows he is going to die. In the actual novel, this part of the story is a bit ambiguous because the reader doesn’t quite now if Ikemefuna knows of his imminent death. Dash filled in this gap, displaying Ikemefuna as slightly more aware and less oblivious about what was going to happen to him.

KGalloway:

“He stared too long, the men cast their eyes down at their feet too often, Father’s wives spoke too little, the children stayed too silent. “

“assured that these unsteady strides would indeed be my last.”

“sand turned mud from the spilled wine and the spilled blood.”

Katie’s imagery and the way her words flowed together made this even, in my opinion, more interesting to read than the original. The progression of the story shows Ikemefuna to slowly become more and more aware. This takes the reader on an interesting journey. Additionally, katie does a very good job of appealing to the reader’s emotions. The story was very melancholy and eery, and I could clearly imagine what Ikemefuna was feeling once he realized that he was destined to die.

Dash: While listening to this story, the revelation of Ikemefuma’s feelings towards his biological father struck me for their insight into the complexity of father-son dynamics, in which individuals reject their fathers in favor of opposite role models; essentially, the “grass is always greener on the other side” mentality. Ikemefuma had “never been too fold of [his] real father,” and took an immediate liking to Okonkwo: similarly, Okonkwo resented his father and strived to be his opposite, and Nwoye, Okonkwo’s biological son, feels alienated by Okonkwo and eventually leaves his tribe. In each of these relationships, Achebe demonstrates that the relationship between a father and soncan lead sons to try and distance themselves from their fathers, no matter who their fathers are, when fathers try to exert control or influence over their actions.

ReplyDeleteKatie G: Over the course of your story, I found that your use of vivid detail in describing emotion, physical characteristics, and the passage of time were particularly compelling and added a layer of depth and surrealness to the story. Particularly, your use of adjectives and descripting adverbs made the story evocative: sentences like “Light-hearted conversation amongst the men was reduced to the infrequent exchange of words as the land between our feet and Umuofia stretched until the low buildings of the village were nothing but slight inconsistencies in the even landscape” allowed a reader to truly envision the setting, and when the action happened somewhat suddenly, the chaos of “spilled wine and spilled blood” juxtaposed with the calm, consistent amosphere you had described.

Katie P: throughout this piece, I interpreted the perspective of Nwoye, as you told it, as a dichotomy of peacefullness (based on the Church’s encouragement of acceptance) but, beneath that, an underlying resentment of his father. Throughout the story, it was interesting to watch you weave these two themes together: specifically, at the end of the story, when Nwoye refuses to see his father be buried and instead chooses to pray, he is doing so both because his brand of Christianity encourages a peaceful acceptance of others’ actions, but also because his deep bitterness and anger towards his father makes him unable to celebrate his life along with the rest of the village. As a result, I think this duality represents that Nwoye is attracted to Christian faith because of its values, but is partly attracted to its values because he looks for the opposite of his father and his upbringing.

Victor: Within your piece, I thought your use of colloquialisms and casual syntax helped to distance Nwoye from his father and his village. Throughout Things Fall Apart, they speak in much more formal, dry sentences, and Nwoy’e more emotive but colloquial phrases presented a sharp contrast to this traditional language. Additionally, your repeated use of simple, short sentences conveyed Nwoye’s youthful passion for the Christian Church: unlike many of the village elders, who speak in convoluted, winding sentences, Nwoye seems overwhelmed with enthusiasm and relief at the discovery of the Christian church, while Nwoye’s expression of his religious passions are more simple, clear, and straightforward- while he is not as wise as many of the village elders, his convictions are strong and unwavering.

Brennan: Your narrative structure helped to make the storyline more compelling, complex, and resounding. I really liked that you starting with a story of an evening conversation between Okonkwo, Nwoye, and Ikemefuna, as it immediately established their family dynamic: while there are tensions and underlying conflicts between the three of them, Okonkwo is a father figure to both Nwoye and Ikemefuna. These intitial stories conveyed the normality of their relationship, which, when Ikemefuna was killed by Okonkwo just moments later, made the betrayal all the more painful and shocking. By presenting this initial family dynamic, you demonstrate that Okonkwo had seemed to grow fond of Ikemefuna, leading the reader to be surprised at Okonkwo’s final actions and truly illustrating the idea that Ikemefuna is blindsided by Okonkwo’s violence instead of just writing in words that he was surprised or hurt. In this sense, I think that your narrative structure helped to enrich the piece significantly, and I really enjoyed it!

ReplyDeleteYale: Within your piece, I found the syntactical juxtaposition between the dialogue, which was casual and simple, and the journal entries and reflection, which were more grand, sweeping, and condemning. Within the dialogue sections, your depiction of interactions between church officials and members demonstrated a simple relationship in which the church officials often did not understand the cultural traditions of the village, and looked to villagers to clarify them (‘“Who is angry?” “The egwugwu. The elders of the clan dressed up as ancestral spirits.”’) Based on this syntax, their relationship was practical; within their discussion, the sweeping power of God and the fate of their opponents were not mentioned. Contrastingly, the journal entries featured the narrator speaking with indignation and passion on the power and sovereignty of God (‘“For their sins the almighty father will punish them with fire and brimstone and they will eternally suffer in the depths of hell”’) which presented a juxtaposing view of the parishioners; many of them, while seemingly joining the church halfheartedly or just out of curiosity, become passionate about the teachings of the Christian missionaries, which then influence their inner narrative and the way they see others.

HDeverell: Throughout the story, you used a casual, nostalgic style that was very compelling and enjoyable to read, but one particular element of this story that stood out to me was the narrator’s casual paraphrasing of Mr. Brown’s words. Throughout your piece, as Akunna reminisces on his friendship with Mr. Brown, he cites their genuine conversations as part of their friendship, and paraphrases the things he learns from Mr. Bronw. When he casually describes Mr. Brown’s teachings and opinions (examples of sentences include “Mr. Brown and I talked about violence.” and “In the white man’s world, violence is not so easily called upon, not so quickly resorted to”) his choice to paraphrase demonstrates that he actually understood and internalized what Mr. Brown was saying, and that they had substantive discussions in which they talked as peers. Your choice to keep the narrative style nostalgically informal reflected a sense of kinship and understanding between Akunna and Mr. Brown which defied the patterns observed in the relationships between missionaries and indigenous people, and showed the genuine nature of their friendship.

ReplyDeleteCAlonso: I really liked that you employed sound as a motif throughout the piece and conveyed Ikemefuna’s emotions through auditory descriptions, as it gave the reader the ability to vividly imagine the scene from Ikemefuna’s perspective. You began this motif in the first sentence, where you describe the noises Ikemefuna hears while walking away from Okonkwo’s village- he “listens to the loud pounding of the travelers’ footsteps around [him]. The thump thump thump syncs with [his] heartbeat as the silence allows thoughts to fill [his] head.” These two sentences immediately demonstrate that, at the beginning of his walk, he is completely aware of the actions and moods of those around him, and finds calm in the constant rhythm of their walking procession. Soon after, Ikemefuna recounts a time when, as a child, he jokingly hid in a hut but had trouble avoiding laughter (or “giggles”) which would have given his hiding spot away. In describing his childish, innocuous laughter, you conveyed his previous innocence and his maturation since leaving his village. Throughout the piece, you continue to use descriptions of sounds, which each have individual emotional connotations (“they spoke quietly and quickly”, etc.) to demonstrate Ikemefuna’s emotional perspective at different points in the story; as a whole, I think this tactic added a lot to a reader’s sensory experience, and made the story feel real and engaging.

MBecerra: While reading your story, I was particularly struck by the narrative structure you used for the first paragraph- you started with several sentences describing Okonkwo’s life events, opinions, priorities, and grievances, which immediately established that his feelings were considered the most important, and then, in the last section of the first paragraph, the narrator (Okonkwo’s daughter) expressed her own opinions on her homeland and the town she was leaving. I thought that, by starting the paragraph with details about Okonkwo’s life and preferences, you clearly expressed the different roles within Obiageli’s family; her father’s opinion, both literally and figuratively, comes first, while hers is trated like an inconsequential afterthought. Overall, your narrative structure helped to start the piece off with a strong statement on the cultural norms Obiageli is living with.

JOlah: I felt that, in your historical fiction story, your use of syntactical repetition helped to emphasize the emotions Unoka was feeling and made the story more impactful for the reader. You used repetition for the first time when Unoka’s kinsmen were listing his offenses: “You are lazy and wasteful. You are a debtor who owes many cowries. You have taken and sought no titles.” In this passage, your use of repetition helped to highlight the deep-seated divisions between Unoka and his kinsmen because of his failure to become a warrior or farmer: his kinsman lists his grievances in an itemized, organized manner, as though they have been on his mind for many years, and clearly makes the point that Unoka does not contribute to the village. You used repetition as a literary device in several other occasions, including when Unoka says “I care not for blood. I care not for war. I care not for wealth. I care not for titles and fame.” Here, the repetitive structure helps to truly get across to the reader that Unoka does not subscribe to the same goals as his fellow villagers: again, he lists their priorities, systematically declaring his rejection of each. Then, in the next sentence, he says “I have dreams and desires for a peaceful life, and…” a sentence which diverges from the pattern set in the previous four sentences: by arranging the sentences in this order, you highlight the last sentence as unique and breaking the pattern, therefore emphasizing that Unoka’s convictions stand out among the views and priorities of his kinsmen. Overall, your use of repetition as a literary device throughout the peace helped to highlight and emphasize Unoka’s emotion and conviction, which made the piece very compelling as a whole.

ReplyDelete